OPEN WORK

A large part of my work as a soloist revolves around "open scores," works the invite significant input from the performer. Because of the choices available, many different sounding results can often be made from the same score. My work often explores multiple methods of realization, testing the limits of these works.

Systems 1-2 of the Four Systems score.

EARLE BROWN: FOUR SYSTEMS

Earle Brown's Four Systems (1952) is not explicitly a percussion work. Any instruments or sound-producing means can be utilized to create a version of the score, so long as the sounding result bears a relationship to the visual stimulus of the score. The two versions below take different approaches to this material. In the first version for vibraphone and electronics, I precisely measured all of the components of the score and realized them on the vibraphone in different pitch regions. In the second version for amplified cymbals, I chose a path through the given material improvisationally, creating a new version in the moment of performance.

JOHN CAGE: VARIATIONS II

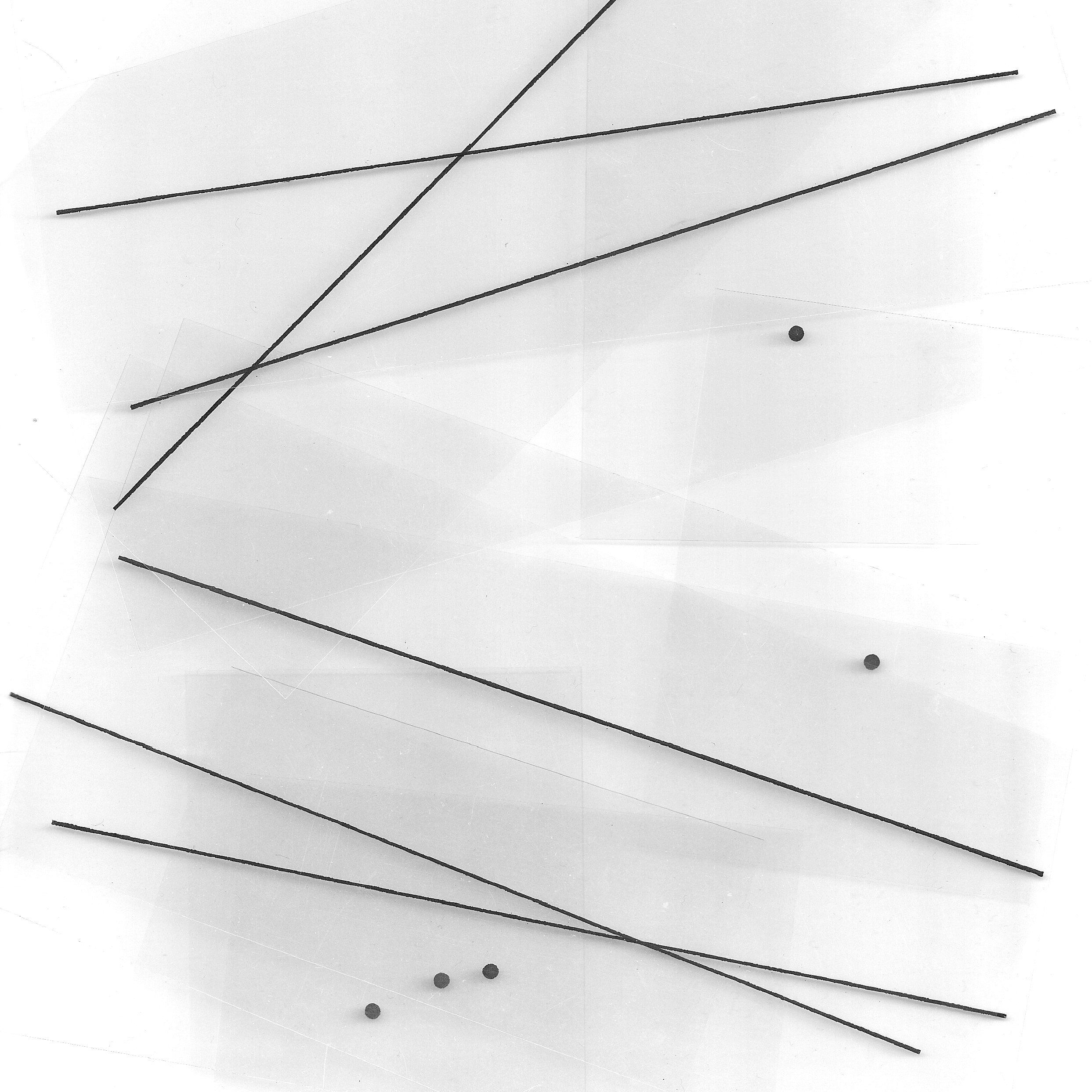

Cage's score consists only of six lines and five points printed on transparent sheets. By arbitrarily superimposing these sheets and measuring the distance from each point to each line, the interpreter generates an interrelated web of numeric data that must then be translated into musical information. Any number of players and any sound sources may realize this data as sound. In my solo realization for four snare drums, I sought a method of engaging with my instrument that is unpredictable and indirect: just as Cage distanced himself from the sounding result of his score, so too would I distance myself from the actual striking of percussion instruments. Here, I control an array of sine tones that sympathetically activate snare drums, creating chaotic webs of pulsation.

Overlaid transparent sheets for Variations II.

One module from Zyklus.

Karlheinz Stockhausen: zyklus

Stockhausen's solo work utilizes a radical form of notation which can be read right-side-up or upside-down. In either case, the performer will always complete a slow 360-degree rotation (clockwise or counterclockwise) around the circular array of instruments over the course of the piece. The performer also navigates small notational modules (like the one seen at left) that provide options for the selection and placement of different musical figures.

JAMES TENNEY: THREE PAGES IN THE SHAPE OF A PEAR

Erik Satie composed his work for piano four hands, Trois Morceaux en Forme de Poire (Three Pieces in the Form of a Pear) in 1903, (allegedly) as a sarcastic rebuttal to Claude Debussy’s suggestion that Satie “pay more attention to form” in his music. Tenney’s 1995 score takes the notion of form literally, providing the interpreter(s) of this piece with a detailed dot rendering of a pear, suggesting the notation be read “in any degree of ‘focus’, from as exact as possible, in one extreme, to very freely, at the other.” My version takes the former extreme, utilizing microtonal divisions of the vibraphone range to render the contours Tenney’s pear in precise detail.

Excerpt of the Imaginary Landscape No. 5 score.

John Cage: Imaginary Landscape no. 5

Cage’s Imaginary Landscape No. 5 consists of instructions for the assembly of a work on magnetic tape. The score provides information for the duration, amplitude, and channel of each sound, cut together from any forty-two records. In preparing a version of this score for computer audio technologies, I built a program that generates versions of Imaginary Landscape No. 5 in real time, using any forty-two recordings on the computer’s hard drive. The first version below is generated utilizing recordings of Johannes Brahms' orchestral works, while the second version below employs a catalog of early electronic music.